Last updated on October 10, 2024

by Priya Saxena

Prism Stalker: The Weeping Star, by Sloane Leong with letters by Lucas Gattoni, is the second volume of the Prism Stalker graphic novel series. In this volume, Vep continues training to become a Scout and furthers colonization efforts on the planet Eriatarka. She becomes more comfortable wielding pneuma, the uncanny energy of the planet, but as the brutality against the indigenous life forms of Eriatarka escalates, she feels more and more conflicted about her choices.

Vep trains and weighs her options with her friends at the Academy while discovering more about Eriatarka, the colonization efforts, and the consequences of the path they’ve chosen. BoC had the opportunity to interview Sloane Leong about Prism Stalker: The Weeping Star, out August 2 from Dark Horse.

The universe you’ve created for Prism Stalker has an incredible variety of alien species — I can only imagine how much work must have gone into designing all of them. That being said, Vep, the protagonist, looks basically human. In a universe populated with so many non-humanoid aliens, why give the protagonist a humanoid appearance?

Even though non-humans and non-human personhood are a huge part of the themes and plot of the story, the indigenous perspective is still the focus. I wanted to visually foreground a portrayal of indigenous people which we get with Vep and her family in a fictional analogue. I have many other stories, particularly a lot of short fiction, that centers non-humans as the protagonists from aliens, salamanders, to sentient houses but for this particular story the human relationship to non-human life is what I wanted to explore.

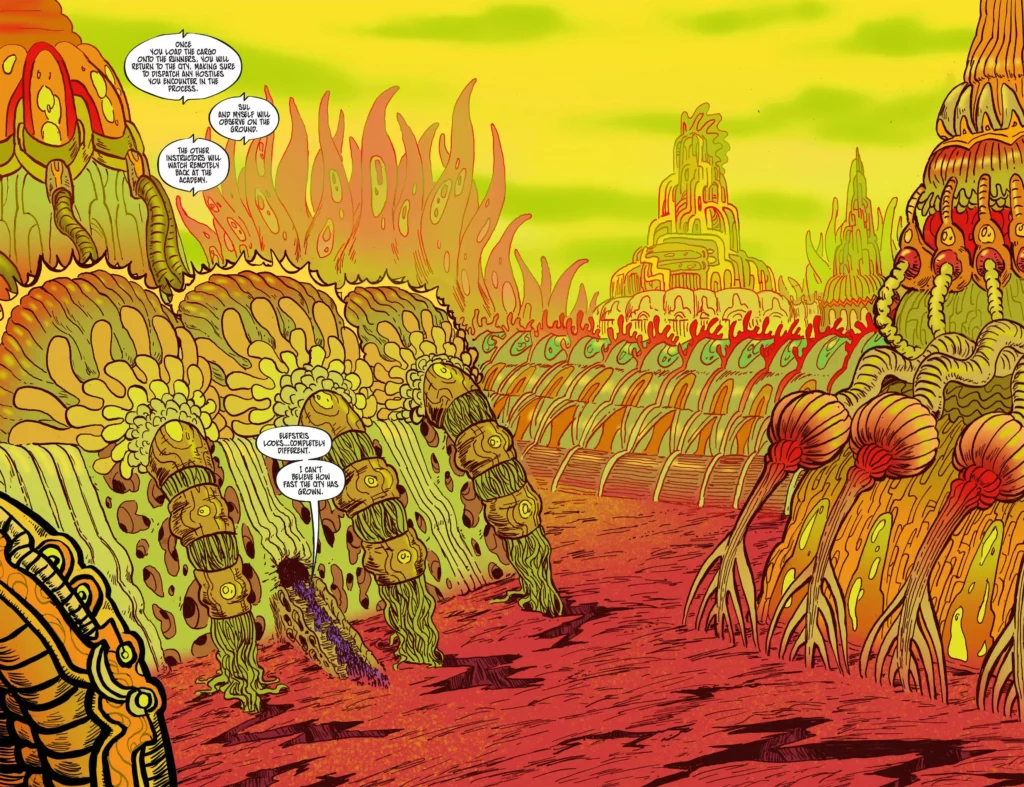

The cities and landscapes of the planet Eriatarka are mesmerizing to look at, lush as they are with colorful flora in intriguing alien shapes. Eriatarka’s fauna is also fascinating, particularly in the way it fights back against the invaders trying to exterminate it. One of the consequences of colonization is ecological damage — colonizers “taming” ecosystems they know little about and throwing them out of balance. Can you speak to the attention you give to the plant and animal life of Eriatarka and how you use it to tell a story about colonization?

Animals, nature and the delicate ecologies we humans exist in has always been fascinating to me but especially fascinating and horrifying is the lengths humans will go to satisfy ourselves at the expense of our environment and fellow animal life. This isn’t a profound source of inspiration. But what I wanted to do with Eriatarka was speculate on a world where flora and fauna, normally silent and subject to human will, were given personhood and could force their personhood on those around them. The only other piece of literature that grapples with this sort of ‘everything is alive’ setting is Hylozoic, an oddball spiritual scifi novel by Rudy Rucker.

During one mission, Vep is overwhelmed by the stark realization that what she is doing to the indigenous life forms of Eriatarka is essentially what was done to her family. Out of all the students, Vep is the most resistant to performing the wanton cruelty the Academy demands. She more easily identifies with the Eriatarkan life forms she is asked to cull than her fellow students do. Yet she remains at the Academy. When formulating the ways Vep attempts to justify her actions to herself, did you have in mind examples of real life individuals from marginalized backgrounds who side with their oppressors and turn on people like them?

Not any single individual, no. This conflict was inspired by how we all make choices which contribute to the communal hell we currently live in. There is no one alive, marginalized or not, that is untouched by colonization, both as an oppressed person and an oppressor. Obviously some people/groups/cultures have more power than others to exact their will on others but it is not an either/or label. If you live on unceded land, if you contribute passively to the destruction of our natural resources, you are an oppressor. If you live under a racist, capitalist, imperialist hegemony, you are oppressed. Everyone exists as both and to think otherwise is to position yourself as culturally or societally innocent but innocence doesn’t exist in that capacity, not in the world we’ve made.

Vep’s external and internal struggle to untangle this impossible knot of complicity is meant to reflect our own plight in this imperialistic, war-mongering world. For Vep, she grapples with the question of whether rebelling against or reforming this galactic governance is the best option. There is a galaxy full of alien species the Chorus has brought into harmony but the cost is controlling and dividing up resources like the planet of Eriarka provides. As always, it is a question of greater goods and lesser evils.

Friendships develop between Vep and some of the other students at the Academy, yet Vep and her friends are all very different from each other. They have different reasons for joining the Academy and different perspectives toward the work they do; Tura insists that what they do is for the greater good, while Sabrian has no illusions about how awful it is. How do Vep’s friendships complicate her own morals and objectives?

Yes, the constellation of motivations all exacerbate Vep’s struggle even more. Tura and Sabrian and the other students have rational reasoning behind their choice to join the Academy and work for the Chorus. The simple fact is there is no easy answer; the Chorus does a lot of good and holds much of the galaxy’s millions of species and cultures in equilibrium. But like all great societies, there’s the Omelas element at play: something, somewhere, is being sacrificed to maintain it. So what is the better option: monoculture and assimilation with a view towards peace? Or preservation of vastly different cultures and languages which innately invites conflict? For the Chorus, the answer they’ve opted for is the former and Vep is facing the effects of that choice.

There’s a good amount of body horror in this graphic novel, especially whenever factures are involved. Vep and her friends commit atrocities that change them, and the body horror episodes literalize that change. Given that you co-edited the horror anthology Death in the Mouth, you obviously have an appreciation for horror. What do you feel is the potential for body horror imagery to address the effects and consequences of real-life atrocities such as colonization?

In Prism Stalker, exploring colonization both on a societal and personal level in tandem was important to me. The language we are taught shapes how we view the world and how we communicate to others shapes how others view us and vice versa. We exist within a constant exchange of power and that isn’t always inherently bad; it can be a process of exchange, mutation, and transformation. There’s also a level of biological colonization happening as well, as all of the Academy students get an implant of crystalline material from the planet itself which begins a process of incorporating them into the greater ecosystem. But a lot of change, especially when it’s imposed upon you by someone else or your own body, is intensely unsettling on a physical and psychic level and I try to convey that through the imagery in the comic.

Sloane Leong is a cartoonist, illustrator, writer, and editor of mixed indigenous ancestries. Through her work, she engages with visceral futurities and fantasies through a radical, kaleidoscopic lens. She is currently living on Chinook land near what is known as Portland, Oregon with her family and three dogs.

Priya Saxena (she/her or they/them) is a writer and critic based in New York City who enjoys reading queer comics and watching campy television. You can follow them on Twitter at @lettersofpriya.