Last updated on October 10, 2024

by Priya Saxena

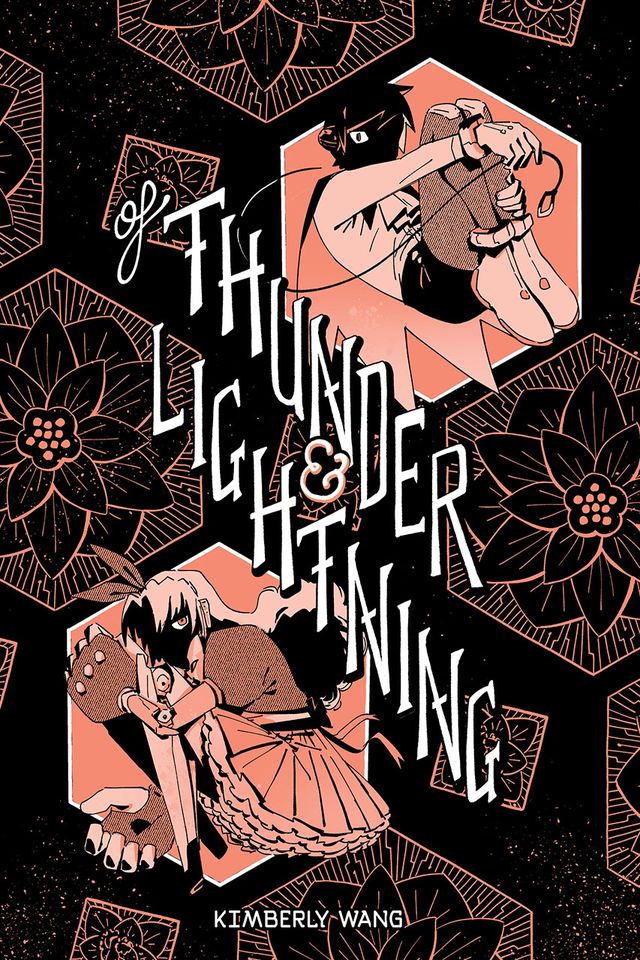

Kimberly Wang’s Of Thunder and Lightning is a two-tone sci-fi graphic novel about two girls who have been conditioned to become celebrity supersoldiers, fighting on opposite sides of a devastating war in a dying land. This is not only a war of physical violence, but also one of propaganda through media and pop culture.

Magni is an aspirational icon to many, but the only time she is with someone who truly understands her is during her battles with Dimo. Yet understanding her doesn’t mean she wants to kill her any less. BoC had the opportunity to interview Kimberly Wang about Of Thunder and Lightning, on sale now from Silver Sprocket.

Given that media propaganda is such a key part of the war, Magni’s costumes and catchphrases are just as crucial to the war effort as her super-strength and blast abilities. I enjoyed seeing bits of in-universe propaganda such as the “sidebar ads” using Magni’s image to encourage enlistment in the war. Such propaganda is of course prevalent in real life, but it tends to skew more masculine, at least in the United States. But in your comic, the military propaganda has a more cutesy aesthetic and seems to be aimed at young girls. What were you interested in exploring by telling a story of young female super-soldiers being used as war propaganda?

In college, I took a class about analyzing depictions of the environment and nature through comics (this will be related, I swear!). In that class, we were discussing climate change and its politics, and I remember our professor stated that, among other things, “climate change is a cultural issue” (paraphrased from memory). In context with having spent the semester learning to read text beyond what might not necessarily be the author intention, and use it as a window to understand it as a reflection of culture, the idea of authors and artists being cultural workers that have an inevitable hand in shaping or perpetuating popular understandings around certain topics (ex: climate and nature) really struck me.

I’m trying not to make this a whole origin story, so to try and be brief, I started art college for illustration in 2016, graduated in 2020, and took a vague direction towards the entertainment industry by the end of that span. So obviously a lot of things were happening in America during and between and after those years. To try and organize the massive swirl of thoughts in my head I was processing, two threads that become relevant to Of Thunder and Lightning are “nostalgia” and “contentification.”

“Nostalgia” took a lot of different forms and generally was about calling for a return to or evoking an ideal past to soothe or stoke or rally or profit off of people. Creatively, I was seeing the entertainment industry, my future employment path, indulge in these safe choices for the sake of profit. I was also thinking about this link between soft power and hard power, and there are conceptual examples of this but also very tangibly, there are mega IPs that have literal ties to the military. So this weaponizing of nostalgia underpins a lot of my design choices and how the two corporation-nations of the graphic novel operate. The cuter aesthetic of the company propaganda in the book isn’t so much about targeting a younger audience so much as using safe and familiar icons to make dubious messaging and disturbing ideas more palatable. And when you’re in the trickle down employment of one of those companies or IPs, what’s your relationship to all that?

During this time, I felt like the “contentification” of everything was also taking off – influencers and content creators existed beforehand obviously, but it felt like there was this huge momentum behind the idea that now anyone could become a “content creator.” It became this vortex that pulled in artists in both hobbyist and professional capacities. Suddenly you didn’t just have to worry about honing your art and skills and ability to create in order to be successful as an artist – you were part of the content as well.

Basically, a lot of these themes were born of the current events I was taking in and processing, as well as figuring out feelings on navigating a career and industry as a new adult, artist, and worker. What will my relationship to the entertainment and content industries be? What is the balance of responsibility and survival as a cultural worker? Is there even a clear answer to it all?

With science fiction and fantasy literature, there is a need to quickly establish some rules of the world so the reader can follow the action. In this comic, you orient the reader by opening with an in-universe propaganda comic depicting Magni’s origin story as a hero. But it soon becomes clear that this origin story is not completely accurate. It seems to me that the journey the reader goes on in parsing what is true and what is false somewhat mirrors the experience of someone who is being fed propaganda and is trying to determine the truth. How interested were you in challenging readers to rethink their perceptions and figure out the truth for themselves?

This was absolutely one of my interests! We live in a media landscape that becomes more and more sensational by the day, with research and nuance and ambiguity becoming farther and farther from the default mode of intaking information. We’re absolutely inundated with messages signaling “this is good!” and “this is bad!” and if companies and advertisers had their way we wouldn’t have a single breath to think our own thoughts.

I do think it’s really important for people to learn how to take a step back and not just question “Is this supposedly bad thing actually good? Could this thing being marketed as good to me really be bad?” but also be able to discuss things on the level of “Are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ even appropriate ways to view this? In addition to A vs. B, is there a factor C that neither side wants you to think about as a possibility? What information am I missing? What information is being obscured from me?” When thinking is flattened into black and white, good or bad, I think it’s easy to create this category of “other,” where what and who counts as “other” becomes easy to manipulate.

These thoughts are really just my own opinion on the matter rather than a “lesson” in Of Thunder and Lightning, though I try to veer away from that kind of storytelling to begin with. I think my way of holding true to these beliefs was to not use characters to lecture the reader and honestly approach this comic as an exploration of topics like propaganda and being part of the construction of culture, instead of pretending I had some absolute moral and universal answer. I think it’d be the greatest praise for my work to be a text that gives the reader a framework or curiosity to start asking questions of the tangible and intangible institutions around us with a healthy skepticism.

Magni’s primary foe is Dimo, who fights for the Ark Empire. Though they are on opposite sides of the war, Magni and Dimo are, in a sense, the only peers that either of them have. They have similar abilities and serve similar functions in their respective political groups, but their costumes and appearance are very different. Magni has a more tomboyish, sporty look, whereas Dimo is ultra feminine. What were your inspirations for their designs? What do you think their respective costumes and presentations say about the factions that created them, and how they are viewed by these factions?

The theme of Magni and Dimo’s character designs is to embody icons of nostalgia, with each design pulling elements from childhood cartoons or big cultural characters, just remixed and regurgitated enough to claim originality while evoking familiarity. Magni has elements of Mickey Mouse, Robin, and Nezha (a Chinese mythological figure; I loved watching one of the Chinese cartoon series as a kid. He’s a pretty popular figure to do reimaginings of now). Dimo is a mix of Powerpuff Girls, Sailor Moon, and Vocaloid. In general, I wanted to give them a somewhat trope-y and toy-like look, and they initially had much more chunky proportions. I wasn’t used to drawing like that though and they ended up with more normal proportions.

In-universe, the design traits chosen are somewhat arbitrary to each iteration, with micromovements towards one visual direction or another as probably some test audience’s average taste. Perhaps at some point, a new design had a motivation and direction, but eventually it all gets sanded down into the same mold with a different, referential bow on it. I imagine Magni and Dimo lines likely have swapped costume themes in the past, because to their companies, none of the images and symbols really mean anything beyond being a tool for war and profit. The character personalities implied by their costuming are similarly just whatever the company thinks will move the most merchandise at the time.

You employ a lot of plant and flower imagery with Yggdrasil, which is fitting given its name. Magni is known as the Flower of Yggdrasil, though she also refers to herself as a weed. The scientists who engineer and maintain Magni’s augmentations are known as Gardeners, and one of them gives Magni the nickname “Dandelion.” Yggdrasil’s base of military operations incorporates floral designs even though it appears that no flowers remain in this dying land. What is it about the juxtaposition of plants and military technology and propaganda that interested you? What are your thoughts on how a plant can be labeled both a flower and a weed?

Honestly, in the beginning the visual pairing of mechanical and organic was a coincidence born of following through on other established concepts. The main concept being that Magni (the in-universe character), is symbolized by the lotus, a flower of rebirth, referencing her many iterations to come. And so, the other names followed suit. For the Gardeners, I needed a title for the scientists and guardians of Magni that immediately told the reader what their role was without using space to explain, and also give their job a bit of tonal tension that might prompt some questions. Can someone whose job it is to manage a weapon of war be associated with nurture and care? How might these scientists confront or ignore that dissonance?

Magni and Dimo are referred to as “Weed” and “Vulture” by the opposing corporate nation respectively (and by each other, for fun). I did purposely choose references to living beings that occupy an important ecological role yet have a negative reputation in connotation due to being unpalatable or perceived as “useless.” The easy flip from “Flower” to “Weed” and “Angel” to “Vulture” is part of the exploration of how easy it is to use rhetoric to turn people into a simple “other.”

Going back to the intertwining of mechanical and organic, the flower motif in the architecture ended up folding into one of the ominously positive themes of the book: you cannot kill the living being inside of you. You cannot be rid of the ugly beating heart within you; you will always be human; you will always crave connection; you will always bear responsibility. There will always be hope. And that’s a threat!

There’s a narrative interlude that includes what seem to be job interviews with various Gardeners along with in-universe war propaganda. The interlude allows the reader to take a moment to process a shocking event on the previous pages, and it also provides the reader with more information about the world of this story in a concise way. I found the visual layout of the interview pages to be very ominous and intriguing. What made you choose to include this interlude, and how did you land on the idea of depicting job interviews?

The interlude was originally an extra idea that wasn’t part of the base comic, but as I was working I got so fixated on the concept that I had to include it! I’m a big fan of the anime director Kunihiko Ikuhara and I really enjoy the smart and visually striking reuse and side segments in the different anime series he’s directed. One version of this I especially like is when the segment is radically different from the rest of the series in either form, tone, or both – yet thematically relates to the episode’s events. It may take a bit of thinking to connect the dots, but it helps you appreciate something you may not have noticed the first watch through.

For these pages I was specifically inspired by the shadow play girls in Revolutionary Girl Utena. Using shadow and silhouette to express a mix of theater, performance, absurdity, and farce is just so fascinating to me and felt like a great framework for what I wanted to explore with this section. After making the pages, I enjoyed that this Q&A section felt like a bizarre and sudden commercial break, where you aren’t given time to settle your earlier feelings before being thrown on an entirely different rollercoaster, and then back out the other end into the second part of the book.

One of the reasons I decided it was important enough to be part of the base text is to continue the theme of finding a mirror in an “other.” Magni and Dimo are mirrors to each other, but Magni and the Gardeners can also be seen as mirrors, and these characters are mirrors for the readers (not in a 4th wall breaking way necessarily, but in the way that I believe it’s simply true of all media). What do you see when you look at an “other,” and what does that tell you about yourself?

Magni and Dimo exist in this limbo space between weapon of a corporation (emotionless equipment with a task to complete) and “human” (shorthand for a being with agency, willpower, responsibility, and other messy, intangible things), and I like playing with that blurry to nonexistent line. For these interlude pages, I break the more typical immersive paneling language of the rest of the book and take a very confrontational Q&A form. This helps establish an ominous, omnipotent job interview/performance review-like setting, drawing a relation between the corporate setting and the background systems of the world, and as if to flip the camera on these Gardener side characters. They have been like an audience to the drama between Magni and Dimo until now, but by shining the spotlight on them, it begs the question: what about you (Gardeners, me, the reader)? Are you not part of this big, grinding machine as well? Where are you on that line? Are you human?

If readers want to learn more about you and your comic work, where can they find you online?

I’m on twitter at @raveninblue, and at @kmbrlei on instagram and most other sites. My website is also kmbrlei.com.

Kimberly Wang is a queer illustrator and cartoonist currently based in New York. Outside of working in the animation industry, they draw fantasy and speculative fiction comics with a surreal edge. When not drawing or daydreaming about comics, they enjoy roller skating and all sorts of crafty activities.

Priya Saxena (she/her or they/them) is a writer and critic based in New York City who enjoys reading queer comics and watching campy television. You can follow them on Twitter at @lettersofpriya.