Last updated on October 10, 2024

by Priya Saxena

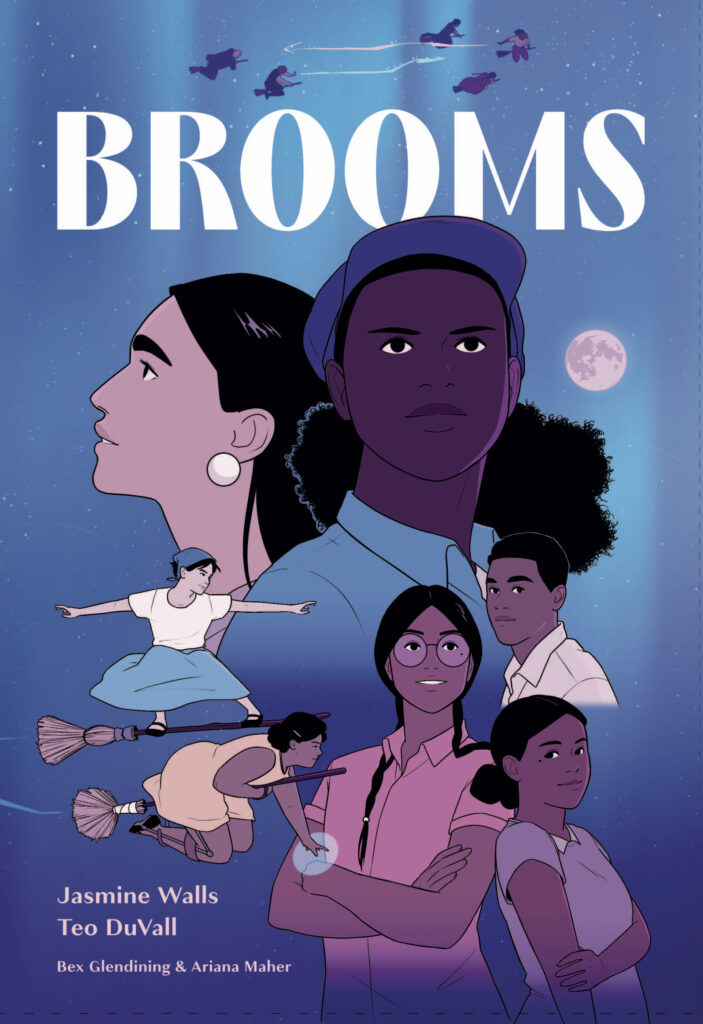

Brooms, written by Jasmine Walls, drawn by Teo DuVall, colored by Bex Glendining, and lettered by Ariana Maher, reimagines 1930s Mississippi as a place where magic is practiced by some and barred from others, depending on one’s heritage. Illegal broom races are a haven for anyone who’s different to prove their skills and earn some cash.

This lively young adult graphic novel follows Luella, a woman whose magic was taken from her, as she devises a way for her younger cousins to avoid being sent away with the help of her lover Billie Mae and Billie Mae’s broom racing teammates. The book blends fantasy with history to explore how people of marginalized groups have always resisted oppression and sought community and solidarity. BoC had the opportunity to interview Jasmine Walls and Teo DuVall about Brooms, on sale now from Levine Querido.

The viewpoint character for this story is Luella, a woman who seeks to help her younger cousins develop their magical skills even though she herself cannot use magic. Luella practiced magic in her youth, but her powers were forcibly sealed away by the government after she defended herself from mistreatment. Despite her inability to use magic, Luella is a very proactive character and hatches ingenious plans to keep her loved ones safe. Still, she misses magic and sometimes wishes she could partake in the thrilling broom races that her friends participate in. I was intrigued by the choice to tell this story from her perspective. Why tell a story about magic and broom racing through the eyes of someone whose ability to do those things was taken from her?

Jasmine: I love hearing from folks who read the book who they choose as the viewpoint character, because it changes each time. When I first came up with the idea, Billie Mae was actually the “main” character the plot was built around, but as I wrote, Luella became the anchor of the story. Each of the girls gets spotlight time in the comic, but Luella’s perspective is special because she’s the only one who has already faced the consequences of being caught and punished with having her magic sealed away. That trauma has had a lasting effect, but I didn’t want her to just exist as a warning. She’s an active part of the story, a quiet mountain of strength, often overlooked but with an immovable conviction. Out of all the girls, her character changed the most from concept to final draft, and she became so much stronger for it.

This graphic novel has a fun and exciting tone overall, and the cute art style and pleasant color palette definitely add to that. However, the book delves into serious historical oppression and atrocities such as residential schools, transphobia, and the banning of Black athletes from playing professional sports. You do an excellent job of telling a story that is ultimately optimistic and heartwarming but doesn’t gloss over the hardships faced by people of color and queer people in 1930s Mississippi. Did you have any strategies for balancing these different aspects of the story so that neither overwhelmed the other?

Jasmine: The balance between discussing serious topics and letting the girls have fun was a tricky challenge, but one I really enjoyed. I wanted to make sure to acknowledge that having magic doesn’t make these societal issues go away, but also that while life isn’t easy for these girls, there is so much joy they can still experience in their community, their chosen families, and in themselves. I never wanted to write a book about The Struggle. This is a book about hope, friendship, and just how far those can take you. Teo’s art and Bex’s colors do an amazing job of translating those emotions onto the page.

Teo: Jasmine wrote such an incredible cast of characters, and I knew that the art needed to reflect the humanity at the core of the story. The people at the heart of Brooms were key to making this story more than something about The Struggle, so I approached the visuals with a lot of focus on expressions, facial details, and hands. People are a huge inspiration for me, and I really enjoy bringing character acting into my comic work. My hope is that those little details bring an air of tenderness to the experience while the book broaches some difficult social issues.

There is a real life history of marginalized communities being accused of “magic” or “witchcraft” by the dominant group and being punished for these practices, which tend to be cultural knowledge passed down from older generations. Much of the magic in this book leans more toward the lighthearted, secular ideas of witches riding broomsticks and D&D-esque magic spells. However, there is definitely an awareness of the history of marginalized groups being persecuted for practicing magic. As in real life, the white men in positions of authority in this story fear the ability of magic and ancestral knowledge to strengthen and empower marginalized communities. How did you seek to weave that history into this story, and why was it important to you to incorporate it?

Jasmine: I spent many years in my teens and twenties involved in Pagan circles because most of the friends I was close with at the time were various flavors of Pagan, so I never think of magic as being this one single structured system. I try to avoid the very Eurocentric idea of magic all in Latin, especially with the long history of BIPOC having their own religious and ritual practices erased, stolen, or ridiculed. Since none of the girls in Brooms have attended the magical academies, they would have no reason to have learned a rigid Latin-based magic style, and they rely on magical knowledge passed down through their own cultures and families or shared in secret from one another. The Brooms and D&D style spells are definitely more secular, and easily recognizable, since we needed something that would work well with anyone’s magic, but I hope we dropped enough clues to make it obvious that despite the government’s claims, there is no “right” way to do magic.

Languages other than spoken English are occasionally used in this graphic novel. Luella and some of her family members are sometimes shown speaking Chahta, while Luella’s younger cousin Emma is deaf and communicates through sign language. Their friend Cheng Kwan, a Chinese American woman, speaks in Cantonese to her mother at one point. For the most part, translations are not used, but it is easy to grasp the general meaning of what is being expressed through context. I was curious about your choice not to translate everything into English and why you felt that was important to the story. I also wanted to ask about the process of including a deaf character who uses sign language in this story, and the opportunities and challenges it presented.

Jasmine: We wanted to make this world feel immersive, and real life doesn’t come with subtitles. Context clues will give readers everything they need to follow the story, but I hope it also helps anyone who knows those languages feel seen and involved. We did consider using subtitles, but I honestly don’t think English should be the default every other language has to be linked to in media. As for Emma’s character, I wanted to explore what her journey might look like as a deaf sign language user, and one who hadn’t gone to school for ASL, but used an Indigenous sign language. We referenced a book called “Indian Sign Language” by William Tomkins, which is not regionally accurate, but is the only extensive illustrated guide of an American Indigenous sign language from the time period that I could find while doing research for the book. One challenge was that for the sake of space in the book, we did have to rely on the very unrealistic concept of Emma being able to lip-read. Teo did an incredible job of translating the signs to the page, and can explain that part of the process better than I could.

Teo: Incorporating American Indigenous sign language was one of the most interesting challenges I’ve ever had to draw for a project, and I loved it. In the script, every time someone signed Jasmine made sure to include the page numbers from Tomkins’ book that I would need for translation, which was a huge help in the process. I’d pose, sign, and take photos so I could have clear reference to work from. So somewhere on my iPad there are a lot of pictures of me acting out these moments while wearing sweats and a beanie pulled down over my forehead. I loved the puzzle-solving aspect of translating hand movement into still images.

I would love to hear about the character design process and how you landed on the looks and clothing of all the characters. It can be a challenge to make everyone look distinctive and instantly recognizable, particularly for a story like this one with so many key characters involved, but you accomplish it very well. I love how a character’s personality shines through from the clothes they wear — Billie Mae’s wardrobe was especially charming to me. What was the collaborative process like to design the visual looks for these characters? Did it involve a lot of research into historical fashions?

Teo: From the start, Jasmine made it clear that I had a lot of creative freedom in designing the girls. It was a pleasant surprise – I wasn’t expecting to have so much input into their designs, and I really appreciated her willingness to share her characters like that. She also provided a lot of constructive feedback that made my designs stronger for sure.

It’s important to me that my characters don’t all look alike, and I put a lot of time into designing each of the girls. I took inspiration from folks in my life, and also studied a lot of archival photographs from the period. I dug through a lot of historical archives and photography books of the era, and from there I took inspiration from key outfits or items that stood out to me.

I learned overalls were very prevalent among working-class folks (namely men), and I knew almost immediately that I needed to outfit Billie Mae in one. Large knit sweaters were also a staple, and I loved the idea of Luella wearing one to cover the sigils on her wrists. I can’t tell you just how many reference pictures I have saved just of 1930s women’s shoes.

Jasmine Walls is a writer, artist, and editor with former lives in professional baking and teaching martial arts. She still bakes (though she’s pretty rusty at martial arts) and has a deep love for storytelling, creating worlds, and building tales about the characters who inhabit them. Along with Levine Querido, she has works published with Boom! Studios, Capstone, Oni Press, The Atlantic, and The Nib. She lives in California with two dogs and a large stash of quality hot chocolate.

Teo DuVall is a queer Chicanx comic artist and illustrator based in Seattle, WA. They graduated in 2015 with a BFA in Cartooning from the School of Visual Arts and have had the immense pleasure of working with Levine Querido, HarperCollins, Dark Horse, Chronicle Books, Scholastic and more. He has a passion for fantasy, aesthetic ghost stories, and witches of color, and loves being able to create stories for a living. Teo lives with his partner, their two pets — a giant, cuddly pit-bull, and a tiny, ferocious cat — and a small horde of houseplants.

Priya Saxena (she/her or they/them) is a writer and critic based in New York City who enjoys reading queer comics and watching campy television. You can follow them on Twitter at @lettersofpriya.